13) Vibrance in Glyphs

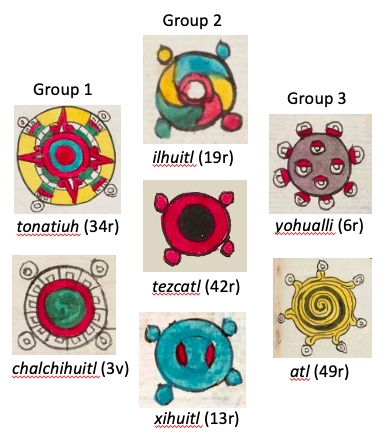

Reviewing Nahuatl hieroglyphs as they enter this collection, especially ones that are beginning to emerge as sharing a similar shape, can lead to some questions about what some of their features signify. The images here include three groups of glyphs worthy of further investigation. Group 1 consists of circular shapes, including concentric circles, plus four smaller circles on the perimeter of the larger circles. These smaller circles on the perimeter have smaller concentric circles, possibly referring to the holes that might be found in beads. Group 2, once again made up of circular glyphs, echo the placement of four smaller circles on the perimeter. In these examples, however, the circles do not have the inner concentric circles. Rather, all of these smaller circles are filled with colors, whether four different colors (as with the ilhuitl) or the same colors of the main circles (as with the tezcatl and xihuitl). Group 3 includes circular glyphs once again, but the smaller circular objects on their perimeter are diverging somewhat more. Still, questions might arise as to why these glyphs are round, what do the smaller circles represent, and what can we make of their particular placement?

Circles have a special meaning and place in Native American cultures. Circular representations of the sun seem to echo the round ball in the sky, and pointed rays could be accommodated in iconography, too. (See the tonatiuh glyph in Group 1). But, not all of the objects represented in the glyphs of Groups 1 and 2 are round in their naturally occurring state. Mirrors, for instance, whether made from mica, pyrites, or obsidian, were not necessarily round from the start, but they were apparently cut into circles. Obsidian often had to be polished. Stone workers seemingly made beads and other round shapes out of jade, by cutting, carving, and polishing them, too. When it came to turquoise, artisans likely found turquoise more readily available in small irregular pieces that were suitable for mosaics, and then they created circular mosaics among other shapes. Perhaps these mosaics echoed the round shapes of water-filled, blue and/or green puddles and ponds, even accounting for their wavy or choppy surfaces where the light could dance.

Taking a look at the glossed meanings given to the glyphs in Groups 1 and 2, one finds that they are all objects that have an inherent ability to shine or shimmer: the sun (tonatiuh), an obsidian or mica mirror (tezcatl), and the precious stones of turquoise (xihuitl), and local jade (chalchihuitl). Light can reflect off of all of them. According to Nicholson and Berger, Fernando Alvarado Tezozomoc spoke of "un espejo relumbrante" ("a brilliant mirror") on a figure of Huitzilopochtli that occupied a shrine at the Templo Mayor in 1487. Could all these objects be described as shimmery or vibrant, akin to Tezozomoc's assessment of the mirror? Is there an iconography imbedded in all these glyphs that would uphold the possibility of vibrance? Vibrance and shimmer are less passive than gleam or shine, and they imply movement.

The vibrance or shimmer of the tonalli ties in here. The tonalli is a "vivifying force understood by Nahua people of the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries to reside in and animate the body" (Allison Caplan, 2020, 384)--along with animals and objects. Caplan also quotes Jill Furst as asserting that "tonalli could be projected into precious gemstones and rich feathers," and she cites Justyna Olko (2014) for identifying how "feathers, gold, precious stones, and flowers, were identified as the tonaltin of rulers and nobles." Finally, the verb tona (at the root of tonalli) means to shine or give off heat (Caplan, 2020, 386). It may well be that the glyphs represented on the left all have a shimmer and vibrance that reflects the tonalli that Nahuas believed them to possess. Tonalli glyphs consist of a grouping of four circles with smaller concentric circles, reminiscent of the "corner" circles on Groups 1 and 2 here. The tlacuiloliztli glyph, which may really mean ilhuitl, also has the four corner dots.

The small exterior circles on the sun and the jade stone with the interior, concentric circles inside them, are reminiscent of the droplets that, together with the turbinate shells, splash off of glyphic representations of currents of water. (See the atl glyph in Group 3, for example.) Water naturally reflects light and acts as a mirror. Some scholars see the small concentric circles coming off of streams or bodies of water as chalchihuitl (jade, or jade beads). If they are taken as beads, probably polished to a shine much like the discs that were worn by people representing divine forces, then perhaps they suggest a vibrance, too--shine upon shine. The turquoise and jade glyphs themselves, however, have these four small circles functioning as "eyes at the four corners, that is, sending out rays [of light] in four directions...," and they were "precious stones...lustrous bodies." [See: Eduard Seler, 1904b, 150.]

The intentional repeating pattern of four small circles on the perimeter of the larger circles is surely significant. Marc Thouvenot (2008, Fig. 25, 172, notes the "resplendence" of these circles on the sun). The number four is symmetrical, and symmetry was important to the Nahuas. James Lockhart's study of forms of expression explores this propensity for even numbers such as four and eight. [See The Nahuas, 1992, 396.] The quatrefoil has a recurring reference to the cardinal directions that are at the heart of cosmology.

The particular locations selected in the placement of the four external smaller circles on the glyphs in Groups 1 and 2 could not have been random or a coincidence, but intentional once again. They are located in such a way as to almost provide "corners" (as Seler also noticed) to the circles they were on, being on the upper left and right and the lower left and right, forming a quatrefoil. If a line were drawn between each opposing pair of smaller circles, the result would be an X. In all cases, the glyphs have a center circle, too, which, when added to the quatrefoil, forms a quincunx. The Nahua quincunx has a relationship not only with the earth's cardinal points, including the sun's rising and setting locations, but also (crucially) a vertical axis that links the sun's nighttime resting place in the underworld with and its midday zenith in the celestial realm.

The tonatiuh glyph (in Group 1) expresses some of these ways of conceptualizing the universe. The fact that the tonatiuh glyph is a double teotl glyph underlines the connection to sacred or divine forces. The hieroglyph for ilhuitl (day) is also clearly linked with the sun and the calendars, the day and year counts (tonalpohualli and xiuhpohualli).

Does a vibrance or shimmer emanate from these glyphs, connect them to the sun, and therefore the Nahua universe, with all of its philosophical and religious significance? The concept of "vibrance" is a light that includes movement, having a relationship with vibration. Does movement (olin) enter into the iconography? The example from the Matrícula de Huexotzinco's folio 583 recto seems to have shimmer, as do several others in that grouping. The association between the sun (whose movement is essential) and divine or sacred forces may lend itself to these other precious stones.

The coloring of these possibly shimmering objects varies considerably, along with their iconographic details. The red ring of the tezcatl is something to be watched, given its placement in many glyphs as a liner or passage zone between inner and outer spaces. The chalchihuitl glyph, with the red ring right next to the green, three-dimensional jade bead, is somewhat reminiscent of the red and/or yellow liner that separates the earth from the waterway in the apantli, for example. In a similar vein, the red ring around the obsidian in the mirror may provide a kind of liner akin to the red/yellow liner around the opening of a cave, separating the underworld with the earth's surface, as in this (oztotl) glyph. See also the article about interiors on the navigation bar to the left. The red leaf-shaped details of the turquoise glyph are something of an outlier iconographically, but perhaps they served as some kind of passageway or else a nod to the mosaic work that turquoise sometimes required.

Two more images appearing here (Group 3) point to 1) the previously mentioned vibrance of water--in this case, from the yellow water (atl) glyph of Acozpan (Codex Mendoza 49r)--and, 2) the representation of the night sky as round and full of stars (what some scholars call "starry eyes"). The stars here clearly associated with eyes (perhaps looking down upon us from the celestial realm). These eyes appear around the perimeter of the circle, but also within it, and there are many more than four, perhaps recognizing the uncountability of the celestial bodies. While not quite in line with the other quatrefoil or quincunx shimmery shapes, perhaps the tlacuilos are nevertheless indicating that stars, like eyes, are vibrant or shimmery. López Austin (cited by Caplan, 2020, 386, 390) identifies "shining eyes" in humans as representative of tonalli and notes how the Primeros Memoriales emphasize the shine and mirroring of human eyes.

In all the glyphs selected for examination here, the differential in size of the circles, large and small, and their placement, may cause the viewer to look back and forth, an action that contributes to their vibrance. This could also tie into the continual "struggle of converse entities" that James Maffie (2014, 137–138) discusses in relation to the pairing involved in the concept of namictli and Allison Caplan (2020, 401) explores in connection with the combinations of feathers with and without tonalli. The pinwheel of multiple colors that form the ilhuitl glyph gives it a vibrancy.

Concentric circles can have a similar radiating effect, and several of these glyphs here have concentric circles (especially the chalchihuitl, ilhuitl, and tezcatl). If we think of a target where the circles are red and white or even multiple colors, alternating tones can create movement--something of an optical illusion--for our eyes. The flower-fan behind the name Cuicamaxochitl has these graduating rings, getting larger in circumference as they go out from the center, and alternating between white and red. This ritual object has fringes on each layer, too, which further accentuate the movement.

All of these shimmering glyphs and more--as well as the animated things they represent--stand out in the repertoire of Nahuatl hieroglyphs as special. They vividly reflect the vibrancy and motion that tonalli-charged objects can have in the landscape and in the heavens.

Draft of September 2024. (SW)