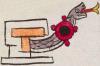

coatl (Mdz20v)

This element for a snake or serpent (coatl) has been carved from the compound sign for the place name, Tezcacoac. The snake here is only half a body, somewhat upright, with its head shown in profile, looking to the viewer's right. Its yellow and red, bifurcated tongue is protruding.

Stephanie Wood

The appearance of the serpent's tongue recalls the glyph for (tletl) (fire or flame) (see below, right). Perhaps the snake's bite caused awe, much as fire did. Serpents did have an association with fire and the fire divinity, Xiuhtecuhtli, as explained by Esther Pasztory (paraphrased by Ian Mursell). The presence of rattles is also important, even if artists often omitted them, because rattlesnakes ware significant in Mesoamerican cultures, as the study of rattlesnakes by Ian Mursell of Mexicolore also elaborates. A wooden, turquoise-mosaic pectoral in the shape of a snake is held in the British Museum, whose curators have written: "The Mexica considered serpents to be powerful, multifaceted creatures that could bridge the spheres (the underworld, water and sky) owing to their physical and mythical characteristics." Besides being an animal that was common in the central highlands, the coatl is the name of the first day of a thirteen-day calendrical cycle.

Stephanie Wood

c. 1541, but by 1553 at the latest

Stephanie Wood

culebras, víboras, serpientes, cohuatl, crótalos

serpent or snake

el serpiente

Stephanie Wood

Codex Mendoza, folio 20 verso, https://digital.bodleian.ox.ac.uk/objects/2fea788e-2aa2-4f08-b6d9-648c00..., image 51 of 188.

The Bodleian Libraries, University of Oxford, hold the original manuscript, the MS. Arch. Selden. A. 1. This image is published here under the UK Creative Commons, “Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 License” (CC-BY-NC-SA 3.0).