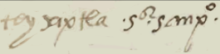

teixiptla (CST16)

This painting appears to represent the simplex glyph for the term teixiptla (or possibly teteixiptla; because of a water stain, it is a challenge to decipher). The teixiptla, in this case, is a religious image in the form of a stretched canvas on a wooden frame. The canvas has lines in the corners that give it a three-dimensionality. Painted on the canvas is a part of an arm with a red sleeve, and the hand of this arm is grasping a vertical key. This iconography points to St. Peter, as the companion text in Nahuatl clarifies, which states that this is a teixiptla of San Pedro. See the transcription and translation of the Nahuatl text from the Codex Sierra in Kevin Terraciano’s study (2021), pp. 111, 147, which explains that the cost of this religious painting that was made (a tlachihualli, something made) was 10 pesos.

Stephanie Wood

This is the first glyph in this collection (as of October 2024) that illuminates the concept of ixiptlatl or teixiptla in Indigenous Christianity. Prior to colonization, a teixiptla might be a figurine that represented a divine force. The closest thing in the database at this time is the nenetl, although it is never glossed as an ixiptlatl or a teixiptla. The nenetl can have the look of a figurine, however, and it is typically shown in a frontal view, looking directly at the viewer, which is a characteristic not usual for humans or animals. Alonso de Molina gives one definition of nenetl as an image of an “idol.” One nenetl image is glossed “teotl.” See below.

James Lockhart (The Nahuas, 1992, 237) writes: "In sixteenth-century texts, one sees ixiptlatl, 'image, replacement, representative,' thus a very good translation of Spanish imagen, which as a loanword appears as well." He adds that by the early seventeenth century the loanword had "won out."

In thinking about how Nahuas viewed the divine forces around them and how they thought about taking on their attributes in dressing themselves or creating images of them, see the Mexicolore page about "ixiptla."

Stephanie Wood

teyxiptla .Sor. sanpo.

teixiptla Señor San Pedro

Stephanie Wood

1550–1564

Jeff Haskett-Wood

pinturas, cuadros, marcos, religiosos, llaves, íconos, San Pedro

teixiptla, a representative of a deity in religious ceremonies before and after colonization (although not seen exactly as a representative, but rather as living), https://nahuatl.wired-humanities.org/content/teixiptla

ixiptla(tl), representative of a divine force, or a deputy, https://nahuatl.wired-humanities.org/content/ixiptlatl

nene(tl), figurine of a divine force, or a doll, or women’s genitals, https://nahuatl.wired-humanities.org/content/nenetl

una representación de San Pedro

Stephanie Wood

Códice Sierra-Texupan, plate 16, page dated 1555. Origin: Santa Catalina Texupan, Mixteca Alta, State of Oaxaca. Kevin Terraciano has published an outstanding study of this manuscript (Codex Sierra, 2021), and in his book he refers to alphabetic and “pictorial” writing, not hieroglyphic writing. We are still counting some of the imagery from this source as hieroglyphic writing, but we are also including examples of “iconography” where the images verge on European style illustrations or scenes showing activities. We have this iconography category so that such images can be fruitfully compared with hieroglyphs. Hieroglyphic writing was evolving as a result of the influence of European illustrations, and even alphabetic writing impacted it.

https://bidilaf.buap.mx/objeto.xql?id=48281&busqueda=Texupan&action=sear...

The Biblioteca Digital Lafragua of the Biblioteca Histórica José María Lafragua in Puebla, Mexico, publishes this Códice Sierra-Texupan, 1550–1564 (62pp., 30.7 x 21.8 cm.), referring to it as being in the “Public Domain.” This image is published here under a Creative Commons license, asking that you cite the Biblioteca Digital Lafragua and this Visual Lexicon of Aztec Hieroglyphs.