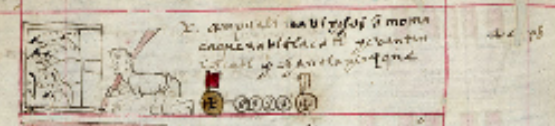

tlapiazque (CST42)

This iconographic scene shows a Mixtec man guarding a sheep pen. He holds what appears to be an agricultural tool, such as a digging stick (huictli in Nahuatl), made of wood and painted pink. Perhaps the man could use it to prod the animals. The companion text refers to four tlacatl (people, likely men) being hired to guard (tlapia) the sheep, even though only one man is shown here. He wears only a loincloth, visible only by the waistband. He is shown in profile, crawling toward the viewer’s left. The verb tlapia appears here in the third-person plural future tense (“they are to guard”).

Stephanie Wood

For more on the Codex Sierra, see Kevin Terraciano’s study (2021), especially pp. 125 and 159 for the relevant Nahuatl language text and English translation. This may be the estancia of sheep that is referenced in earlier pages of this manuscript, where 100 rams were purchased for siring lambs. There are also references to unspun cotton or wool (perhaps more often, wool) in these pages of the manuscript, too. Stock raising was introduced by Spanish colonizers in New Spain, but sometimes Indigenous people not only worked for Spaniards in this capacity but got involved doing it themselves. At the bottom of plate 42 of the Codex Sierra there is another reference to “all those who maintain the sheep pen” (Terraciano, 2021, 159). But stock raising of this sort was more common in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, and by then the men taking on this work were being called caciques.

Stephanie Wood

1550–1564

Jeff Haskett-Wood

guardar, animales, corrales, carneros

tlapia, to take care of, guard, https://nahuatl.wired-humanities.org/content/tlapia

huic(tli), agricultural digging stick, an Indigenous tool, https://nahuatl.wired-humanities.org/content/huictli

guardarán

Stephanie Wood

Códice Sierra-Texupan, plate 42, page dated 1561. Origin: Santa Catalina Texupan, Mixteca Alta, State of Oaxaca. Kevin Terraciano has published an outstanding study of this manuscript (Codex Sierra, 2021), and in his book he refers to alphabetic and “pictorial” writing, not hieroglyphic writing. We are still counting some of the imagery from this source as hieroglyphic writing, but we are also including examples of “iconography” where the images verge on European style illustrations or scenes showing activities. We have this iconography category so that such images can be fruitfully compared with hieroglyphs. Hieroglyphic writing was evolving as a result of the influence of European illustrations, and even alphabetic writing impacted it.

https://bidilaf.buap.mx/objeto.xql?id=48281&busqueda=Texupan&action=search

The Biblioteca Digital Lafragua of the Biblioteca Histórica José María Lafragua in Puebla, Mexico, publishes this Códice Sierra-Texupan, 1550–1564 (62pp., 30.7 x 21.8 cm.), referring to it as being in the “Public Domain.” This image is published here under a Creative Commons license, asking that you cite the Biblioteca Digital Lafragua and this Visual Lexicon of Aztec Hieroglyphs.