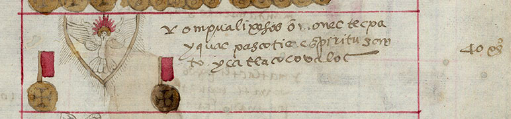

espíritu santo (CST25)

This painting of the simplex glyph for the Christian phrase, espíritu santo (Holy Ghost or Holy Spirit, a loanword that entered Nahuatl from Spanish and, prior to that, from Latin), shows what may be a wall-hanging with an image of this spirit. The image is a frontal view of a dove in flight with its wings and tail feathers opened wide. It has perhaps a crown on its head, with a rounded brown (perhaps once green) shape, and then with ten red points coming out all around that. These red points are reminiscent of a feathered headdress (perhaps red macaw feathers, so prized in Mesoamerica), but if that is the case, this part of the iconography of the Holy Spirit would not have a European origin. The fabric upon which spirit was drawn is wide at the top and comes to a point at the bottom. Thread-like rays come out all around from the border or the cloth, seemingly conveying a radiance that has a divine effect. The companion text says that this was a purchase made by the ruling palace in the town as part of the celebration of the Pentecost.

Stephanie Wood

The use of thin lines to suggest a divine force, which was introduced by Europeans, seems to have caught on among tlacuilos by the 1560s. See some possible examples in the glyphs below. The Holy Spirit is often represented by a crown, but a silver crown. For more on the Codex Sierra, see Kevin Terraciano’s study (2021).

Stephanie Wood

1550–1564

Jeff Haskett-Wood

feathers, ave, aves, pájaro, pájaros, pluma, plumas, animals, animales

This Espíritu Santo is a detail in the painting called “La presentación del Niño en el templo,” by Baltasar de Echave Orio, who painted it ca. 1609–1610. Note the red color around the spirit-bird’s head. The painting is located in the Museo Nacional de Arte in Mexico City. Photo by S. Wood, 4 May 2025.

espíritu santo, Holy Ghost or Holy Spirit, https://nahuatl.wired-humanities.org/content/espiritu

espíritu santo

Stephanie Wood

Códice Sierra-Texupan, plate 25, page dated 1559. Origin: Santa Catalina Texupan, Mixteca Alta, State of Oaxaca. Kevin Terraciano has published an outstanding study of this manuscript (Codex Sierra, 2021), and in his book he refers to alphabetic and “pictorial” writing, not hieroglyphic writing. We are still counting some of the imagery from this source as hieroglyphic writing, but we are also including examples of “iconography” where the images verge on European style illustrations or scenes showing activities. We have this iconography category so that such images can be fruitfully compared with hieroglyphs. Hieroglyphic writing was evolving as a result of the influence of European illustrations, and even alphabetic writing impacted it.

https://bidilaf.buap.mx/objeto.xql?id=48281&busqueda=Texupan&action=search

The Biblioteca Digital Lafragua of the Biblioteca Histórica José María Lafragua in Puebla, Mexico, publishes this Códice Sierra-Texupan, 1550–1564 (62pp., 30.7 x 21.8 cm.), referring to it as being in the “Public Domain.” This image is published here under a Creative Commons license, asking that you cite the Biblioteca Digital Lafragua and this Visual Lexicon of Aztec Hieroglyphs.