Nentequitl (MH627v)

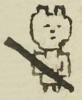

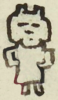

This black-line drawing of the compound glyph for the personal name Nentequitl ("Fruitless Labor" or "Useless Work") is attested here as a man's name. The glyph shows a nenetl (deity image or doll) holding an agricultural tool that has the semantic value of tequitl (work). The doll is dressed in a skirt and has two squared-off protrusions on its head, which could symbolize the neaxtlahualli hairstyle of women. The doll holds the digging stick at an angle across its body.

Stephanie Wood

The black tool the female figurine holds recalls two things, one phonetic and one logographic. The color and rectangular shape suggest an obsidian blade, which is used to cut (tequi). For a photo of a cache of obsidian from c. 1400 in Tlatelolco, see this INAH link. But the way it is being held, it is reminiscent of the huictli, an agricultural tool and symbol of work (tequitl). So, this compound glyph could be partially or fully phonographic.

The vast majority of glyphs or glyphic elements that include the ne- or nen- syllable as a phonogram, typically expressing a negative such as idleness or low productivity, will show figurines in a frontal view. The figurines can be either full bodied, just the bust, or just the head. The syllable comes from the term nenetl, which, as translated by Alonso de Molina, means doll, deity image, or woman’s genitals. These are three very different meanings, although a doll and a figurine of a divine force/deity could have a similar look. The glyphic representations almost always show such figurines, although it can be difficult to tell if they represent dolls or deities. To my knowledge, Alfonso Lacadena (2008a, 21) was the first to publish the interpretation of the nenetl glyph as the phonetic syllable ne-, which in my experience is more typically nen- and which is more likely to have negative implications.

One of the diagnostics for nenetl involves squared-off protrusions on the top of the figure's head. If these are not protrusions such as the glyphs for Cuauhtecolotl or Xolotl have, perhaps they are stylized representations of the hairstyle called neaxtlahualli, where the Nahua sedentary woman wears locks of hair twisted up into two points over each side of her forehead. Fortunately, figurines with squared-off protrusions on their heads have survived from pre-contact times. The Museo Tomás Medina Villarruel has a number of them. These are mostly female, with skirts and bare breasts, and they are often shown in activities such as carrying children or grinding maize. Two images from that collection appear below. These figurines may well be dolls rather than deities.

Ian Mursell has published a photo of such a figurine in an article he shares about rattle figurines. In the image in Mexicolore, the figure on the left fits the nenetl characteristics with its protrusions on its head, and since it is a rattle one could call it a female doll. Other small figurines of women are published in the Museo de Sitio de Tlatelolco (2012, 235); they vaguely resemble dolls and they have interesting headdresses. In that same book, on p. 236, one sees "figurillas femeninas tipo galleta," which are something like dolls that could also be deity sculptures. Again, here, the protrusions of hair at the top of the head more closely resemble the nenetl protrusions.

The five extra days in the calendar of 360 days (xiuhpohualli) were called nemontemi (useless days). It was unlucky to be born on these days. A man who was born in this period was called nenoquich and a woman was called nencihuatl. This is explained in the Digital Florentine Codex in Book 2, folio 12 recto (see: https://florentinecodex.getty.edu/book/2/folio/12r). These individuals were considered unlucky, ill-fated, and even useless. A great many individuals in the Matrícula de Huexotzinco have names beginning with the negative syllable Nen-. Perhaps they were born in that ill-fated period, or perhaps the negative syllable came to be even more liberally applied to names. With men, for instance, Nentequitl ("Useless Labor") was much more common than Nenoquich.

When presented visually, the nen- syllable usually derives from nenetl (a figure or sculpture of a deity or a doll). Nenetl also had an association with women’s genitals, which has caused much speculation about a negativity associated with women and their sex, but that might have come from European religious influence. In the colonial context, such concepts and perceptions could easily become muddied. A few nenetl glyphs or elements in this digital collection do not include the negative nen-, although most do, and most are female, but a few are male or genderless.

Keiko Yoneida writes about the negative reading of nenetl “fetiches” as “useless” or “in vain,” which she suggests is a patriarchal deprecation of women. See her discussion of nenetl and the nemontemi days in the calendar in her study, Los Mapas de Cuauhtinchan y la historia cartográfica prehispánica (1991), 140.

Stephanie Wood

franco,

nētequitl

Francisco Nentequitl

Stephanie Wood

1560

Jeff Haskett-Wood

work, trabajo, labor, laboral, flojo, flojería, cut, cortar, obsidian blade, hoja de obsidiana, deity, ixiptla, deidades, deities, statues, estatuas, esculturas, calendarios, nombres de hombres, axtlacuilli

nene(tl), deity image, doll, female genitals, https://nahuatl.wired-humanities.org/content/nenetl

tequi(tl), work, https://nahuatl.wired-humanities.org/content/tequitl

nentequi(tl), useless work, https://nahuatl.wired-humanities.org/content/nentequitl

Trabajo en Vano, o Trabajador Inútil

Stephanie Wood

Matrícula de Huexotzinco, folio 627v, World Digital Library, https://www.loc.gov/resource/gdcwdl.wdl_15282/?sp=337.

This manuscript is hosted by the Library of Congress and the World Digital Library; used here with the Creative Commons, “Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 License” (CC-BY-NC-SAq 3.0).