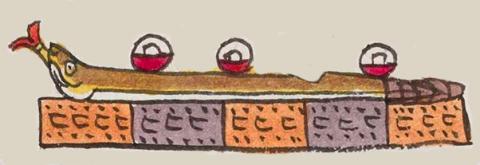

Coaixtlahuacan (Mdz7v)

This compound glyph for the place name Coaixtlahuacan (Coixtlahuaca, today) has three principal elements, a serpent or snake (coatl) on a plain (ixtlahuatl) and three eyes (ixtli). The serpent is very straight, facing to the viewer's left, with its red bifurcated tongue protruding (reminiscent of a flame; see tletl, below). The tongue has a white band around it just below the bifurcation, and below that, the tongue appears to be the same yellow as the snake's belly. The snake's back is a brown color. The three eyes are the standard concentric half-circles drawn in black and largely white, except for the eyelid, which is red. All three eyes are upside-down. The plain is segmented and alternates colors--three terracotta and two purple. The land is textured with dots and u's that are tipped over and look like c's. The -can locative suffix is not shown visually, but it may be represented semantically by the landscape features of the compound.

Stephanie Wood

The eyes (ix-) appear here not with any human anatomical meaning, but rather, to provide a phonetic clue to the reading of ixtlahuatl, and help distinguish it from agricultural parcels such as tlalli, milli, or chinamitl, which have a very similar look. The ixtlahuatl shown here, however, is a bit longer than the usual agricultural parcels, which do not appear in the Codex Mendoza hieroglyphs with more than three segments. Perhaps plains were not always farmed, but a simple rectangle without the typical texturing of land might not have led the viewer to know it was land.

Berdan and Anawalt have suggested that the eyes are intentionally upside down to call forth īxtlapal, which sounds like ixtlahuatl. But Frances Karttunen says that īxtlapal is closer to "sideways" than "reversed" or "inverted." So, she supports the idea of the eyes (ixtli) providing the phonetic start of the word ixtlahuatl. (Source: Frances Karttunen, "Critique of glyph catalogue in Berdan and Anawalt edition of Codex Mendoza," unpublished manuscript.)

Stephanie Wood

Stephanie Wood

c. 1541, or by 1553 at the latest

Stephanie Wood

From the serpent to the plain is a downward reading (from the middle). But the eyes on top provide an added phonetic value that helps with the reading of the plain (which is on the bottom), so that would be upward again.

eyes, snakes, serpents, serpientes, llanos, ojos, cohuatl, nombres de lugares

coa(tl), snake or serpent, https://nahuatl.wired-humanities.org/content/coatl

ixtlahua(tl), plains, https://nahuatl.wired-humanities.org/content/ixtlahuatl

ix(tli), eye(s), https://nahuatl.wired-humanities.org/content/ixtli

-can (locative suffix), https://nahuatl.wired-humanities.org/content/can-2

"Place of the Plain of Snakes" (Karttunen apparently agrees with this translation of the place glyph, although she differes with the interpretation of the eyes.) [Frances Karttunen, unpublished manuscript, used here with her permission.]

"Place of the Plain of Snakes" (Berdan and Anawalt, 1992, vol. 1, p. 179)

"Lugar del Llano de Serpientes"

Stephanie Wood

Codex Mendoza, folio 7 verso, https://digital.bodleian.ox.ac.uk/objects/2fea788e-2aa2-4f08-b6d9-648c00..., image 25, of 188.

The Bodleian Libraries, University of Oxford, hold the original manuscript, the MS. Arch. Selden. A. 1. This image is published here under the UK Creative Commons, “Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 License” (CC-BY-NC-SA 3.0).