14) Multivalence of Footprints

In Mesoamerican art, footprints have clearly left their mark. Three-thousand-year-old eagle footprints carved in stone are known from an Olmec site in the state of Veracruz, Mexico. Artistic representations of human footprints date back at least as early as the Classic period in Mesoamerica. They can be found, for example, on murals at Teotihuacan. In one example, from a piece of mural originating from Teotihuacan (left) and now located at the Dumbarton Oaks museum in Washington, D.C., footprints occupy a space that may be a symbolic path. As Stephen Houston's fifth of six public lectures given at the National Gallery in April and May 2023 showed, some footprints also accompany the presence of foreigners (perhaps from Teotihuacan) in the Maya zone in the fifth century, and single footprints found their way into some Maya glyphs.

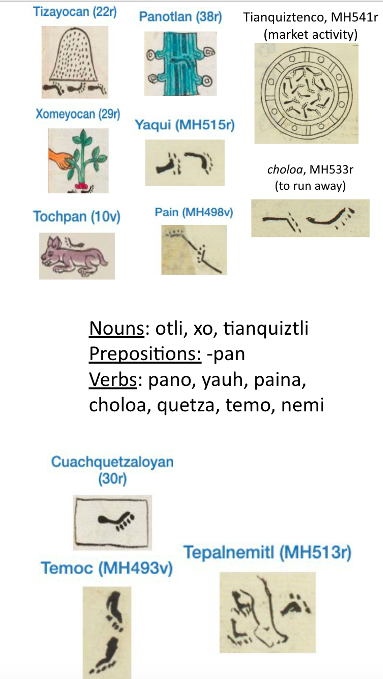

In Aztec hieroglyphs, black human footprints have a regular presence in a wide range of settings and with many different readings. Footprints recall verbs (in alphabetical order), such as "to arrive" (aci), "slip/slide" (alahua), "run away" (choloa), and another verb for "arrive" (eco), "to depart" (ehua, with an example forthcoming), plus "return" (hualiloti), "come" (huallauh), "to run" (motlaloa), "live, walk, go about" (nemi), "travel" (nenemi), "stand" (quetza), "go out/emerge" (quiza), "run fast" (paina), "cross over" (pano), "go down/descend" (temo), "pursue someone" (tepotztoca), "follow" (toca, or "go" (yauh), finding expression in place names and personal names.

Not surprisingly, footprints can also allude to the foot or things relating to it in the form of xo-, as in Texopan, where the foot can also mean "on" (-pan). Footprints come into play in the cases of other nouns, such as cuappantli and, especially, otli (road), whether with a semantic meaning or the phonetic "o." Other semantic uses for human footprints include references to being "at the marketplace" (tianquiztenco) or "on sacred lands" (teotlaltzinco). Finally, "on foot" (iyaquic) is used as a homophone for iyaqui, young warrior, which is a popular name.

Paul P. de Wolf assembled a number of examples of hieroglyphs that employ footprints in his Diccionario Español-Náhuatl. Representative of some of the most numerous attestations, he points to the verbs temo, nemi, and nenemi, among a couple of others.

Carmen Herrera and her co-authors (2005, 64) provide an impressive list of examples showing the multivalence of footprints, and Gordon Whittaker discusses a number of footprints in his book (2021, 100–101). But this database is actively adding to these lists (e.g. with quetza and nenemi), for example. The attestations in the image below will probably still not be exhaustive as this digital collection continues to grow.

Marc Thouvenot generously contributed the glyph for iloa (to return) to this database in a personal communication of 22 December 2024. This glyph represents the place name Tlailotlacan as it appears in the Codex Xolotl.